Epilepsy is a condition that affects the brain and causes repeated seizures, also known as fits.

Referred to as `Apasmara' in Ayurveda, epilepsy, more popularly known as the falling disease, is a serious disorder of the central nervous system that affects both children and adults alike. Afflicting infants and early teenagers the most, it is categorised into two main types – Petit Mal & Grand Mal. Depending on the dominance of the three doshas and their combined effect it can come in four types – a fifth type, called Yoshapasmara, denotes hysteria which is more prevalent among women.

Epilepsy affects more than 500,000 people in the UK. This means almost 1 in 100 people has the condition. Epilepsy usually begins during childhood, although it can start at any age.

Seizures

Seizures are the most common symptom of epilepsy, although many people can have a seizure during their lifetime without developing epilepsy.

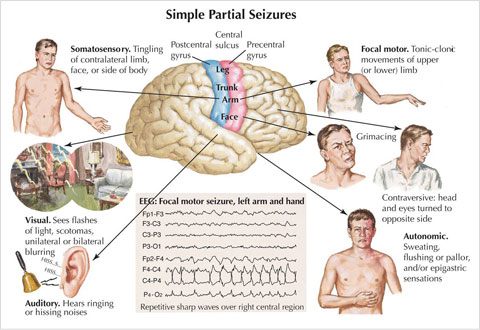

The cells in the brain, known as neurones, communicate with each other using electrical impulses. During a seizure, the electrical impulses are disrupted, which can cause the brain and body to behave strangely.

The severity of the seizures can differ from person to person. Some people simply experience a ‘trance-like’ state for a few seconds or minutes, while others lose consciousness and have convulsions (uncontrollable shaking of the body).

Root Causes

-

Petit Mal results from a strained nervous condition.

-

Grand Mal is due to hereditary influences, serious shock or injury to brain or nervous system and diseases like meningitis and typhoid.

-

Allergic reaction to certain food substances.

-

Circulatory disorders.

-

Chronic alcoholism.

-

Lead poisoning.

-

Use of cocaine.

-

Mental conflict.

-

Deficient mineral assimilation.

Why does epilepsy happen?

Epilepsy can happen for many different reasons, although usually it is the result of some kind of brain damage.

Epilepsy can be defined as being one of three types, depending on what caused the condition. These are:

-

Symptomatic epilepsy – when the symptoms of epilepsy are due to damage or disruption to the brain.

-

Cryptogenic epilepsy – when no evidence of damage to the brain can be found, but other symptoms, such as learning difficulties, suggest that damage to the brain has occurred.

-

Idiopathic epilepsy – when no obvious cause for epilepsy can be found.

Diagnosing epilepsy

Epilepsy is most often diagnosed after you have had more than one seizure. This is because many people have a one-off epileptic seizure during their lifetime.

The most important information needed by a GP or neurologist is a description of your seizures. This is how most cases of epilepsy are diagnosed.

Some scans may also be used to help determine which areas of your brain are affected by epilepsy, but these alone cannot be used for a diagnosis.

How is epilepsy treated?

While medication cannot cure epilepsy, it is often used to control seizures. These medicines are known as anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs). In around 70% of cases, seizures are successfully controlled by AEDS.

It can take some time to find the right type and correct dose of AED before your seizures can be controlled.

In some cases, surgery may be used to remove the area of the brain affected or to install an electrical device that can help control seizures.

Living with epilepsy

While epilepsy is different for everyone, there are some general rules that can help making living with the condition easier.

It is important to stay healthy through regular exercise, a balanced diet and avoiding excessive drinking.

You may have to think about your epilepsy before you undertake things such as driving, using contraception and getting pregnant.

Advice is available from your GP or support groups to help you adjust to life with epilepsy.

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), while rare, is one of the main dangers associated with epilepsy. Every year between 500 and 1,000 people die as a result of SUDEP, this is less than 1% of people with epilepsy.

Although the cause of SUDEP is unknown, a clear understanding of your epilepsy and good management of your seizures can reduce the risk.